Posted September 22, 2016

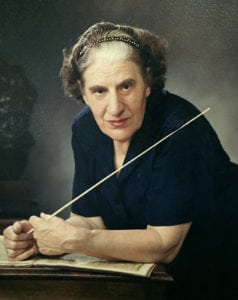

Maestro Antonia Brico, born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands in 1902, moved to California with her foster parents at age 6 and endured a self-described miserable childhood. Though with talent and determination, Brico rose to the heights of the conducting world.

Wilhelmina Wolthius

The maestro was born Antonia Brico but raised as Wilhelmina Wolthius. Suffering abuse by foster parents who never formally adopted her, Wilhelmina found solace at the piano, crying, “Music doesn’t hurt little girls.” It wasn’t until college that she knew the true story of her illegitimate birth to a Dutch teenager and Italian nightclub pianist by the name of Brico.

A rising career

Reclaiming ‘Antonia Brico,’ the aspiring conductor moved to Europe in 1923 and studied under world-famous musicians Zygmunt Stojowski, Karl Muck and Richard Wagner’s son, Siegfried Wagner. Composer Jean Sibelius came to know Brico as a “sixth daughter” after she arrived at his home and proved her ability to conduct his work as he intended.

While studying in Germany, she made her debut as a conductor in 1930. At age 28, Brico led the Berlin Philharmonic earning a glowing review which stated that she “possesses more ability, cleverness and musicianship than certain of her male colleagues who bore us in Berlin.”

In 1934, she founded the Women’s Symphony Orchestra in New York to “prove that women could play in every category.” The successful orchestra garnered support from the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt.

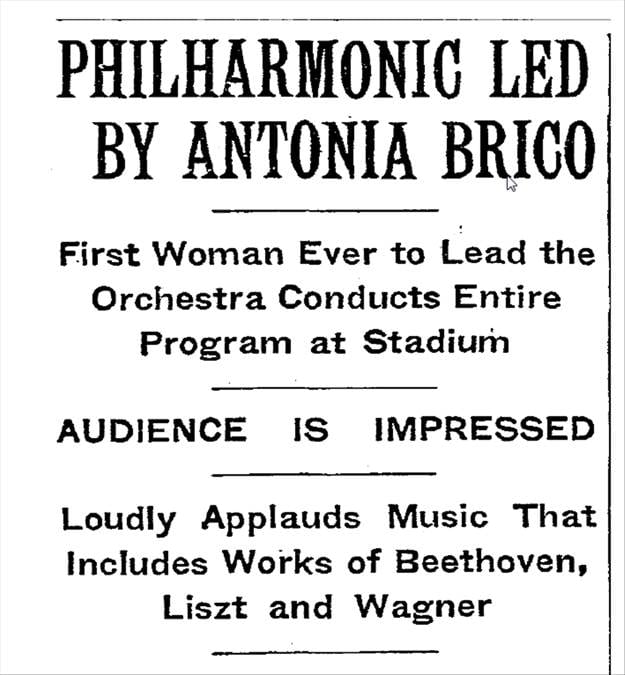

July 25, 1938, Brico conducted the New York Philharmonic — the first woman to do so. Ms. Brico, age 36, impressed the crowd at Lewisohn Stadium, the Philharmonic’s then outdoor summer venue in Upper Manhattan. She conducted works by Tchaikovsky, Liszt, Sibelius and two pieces you’ll hear September 30, 2016 in her honor — Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3 and Wagner’s Overture to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

The New York Philharmonic archive department writes, “Tickets [to Brico’s debut] cost 50 cents and [stadium] crowds could grow to over 15,000.”

The New York Times reported of Brico’s performance that she “impressed” with the “life [and] color of her readings,” expressed with “verve and intensity,” and ended with resounding applause.

“She was the first woman to achieve national acclaim as an orchestra conductor,” long-time Denver Philharmonic violinist Pauline A. Dallenbach said.

A new home

Lured to Denver in the early 1940s with the possibility of becoming the principal conductor of the Denver Symphony, Brico was a guest conductor at concerts in Red Rocks amphitheater but was never hired. The handsome, debonair — and male — Saul Caston won the job.

“She told me it was the greatest disappointment in her life,” Dallenbach told the Westword in 1995.

Despite her talent and drive, Brico seemed to only have conducting opportunities during World War II when most men were serving. She said that she was born 50 years too early.

Brico settled in Denver in 1942 and made her home here. Legions of Denver musicians took piano and voice lessons with her. Sometimes she enlisted students to walk her dog before or after a session. A busy woman with no relatives, she was known for asking favors.

Her next position was as the founder and first music director of the Denver Businessmen’s Symphony in 1948. At the premiere performance, Brico received a telegram from Sibelius wishing the new orchestra luck. The orchestra’s name later was changed to the Brico Symphony in the 1960s, Centennial Philharmonic in the 1990s and finally — you guessed it — the Denver Philharmonic in 2004.

As a child, Greeley Chamber Orchestra conductor Dan Frantz described seeing the maestro conduct the then-Brico Symphony, “She wore this huge, black, flowing velvet gown. … It just absorbed light and drew your attention right to her. And she had this stern look on her face that could have melted parts of Greenland.”

Lasting friendships

She had an enduring friendship with Dr. Albert Schweitzer, the organ-playing doctor who practiced medicine in the wilds of Africa. The two shared a love of Bach’s music, and she detoured home from an engagement in Europe to visit Schweitzer in Africa in 1950. He had inscribed to her “with love,” a copy of Stravinsky: His Life and Work, which is now in a private collection.

Denver Philharmonic Board Member Eleanor Glover even recalls how Brico transported autographed photos of Schweitzer and Sibelius for one another between Africa and Finland.

The broader music world’s interest in Brico was rekindled in 1974 when her former Denver piano student (and later famed folk singer) Judy Collins and director Jill Godmilow made a documentary film A

Antonia: A Portrait of a Woman. The following year, she was invited to conduct at New York’s Mostly Mozart Festival and in 1977 at the Brooklyn Philharmonia. The event was sold out immediately and a second performance was added. It was captured on LP recording.

Brico’s legacy

Brico retired in 1985 and passed away in 1989. There are still people involved with the Denver Philharmonic like Pauline Dallenbach and her husband Robert, who knew Antonia personally.

Mrs. Dallenbach, who began with the orchestra in 1964, remembers Brico saying she “taught and inspired many musicians.”

“In honor of Antonia Brico, the first woman to conduct the New York Philharmonic, in 1938,” the symphony orchestra writes, ”[we] salute the Denver Philharmonic as they inaugurate the Antonia Brico Stage. … We wish the Denver Philharmonic many such nights from their newly dedicated stage.”

Thank you for being part of our history on September 30 as we honor Brico and inaugurate the Antonia Brico Stage at Central Presbyterian Church!