Claude Debussy

La mer (The Sea)

“You’re unaware, maybe, that I was intended for the noble career of a sailor and have only deviated from that path thanks to the quirks of fate. Even so, I’ve retained a sincere devotion to the sea,” wrote Claude Debussy to a friend in 1903, as he began work on La mer. Debussy’s connection to the ocean began in his childhood when he made several extended visits to Cannes. Interestingly, when he commenced the writing of La mer, the sea’s allure worked so powerfully on Debussy that he took himself off to the mountains near Burgundy, safe from ocean’s siren call. “I have innumerable memories,” Debussy continued in his letter, “and those, in my view, are worth more than a reality which, charming as it may be, tends to weigh too heavily on the imagination.”

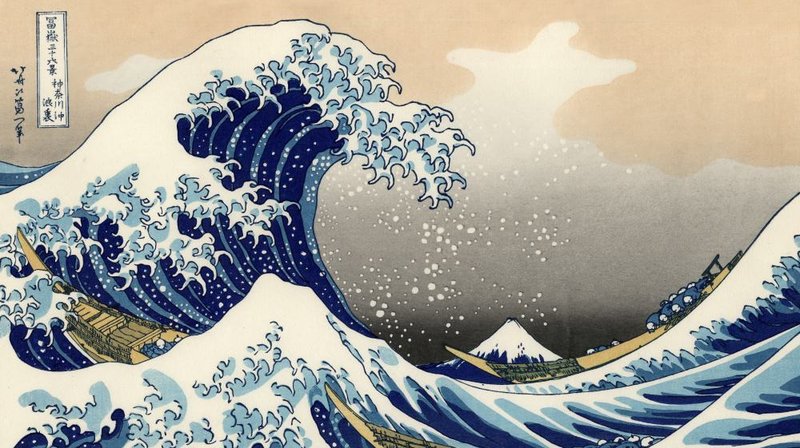

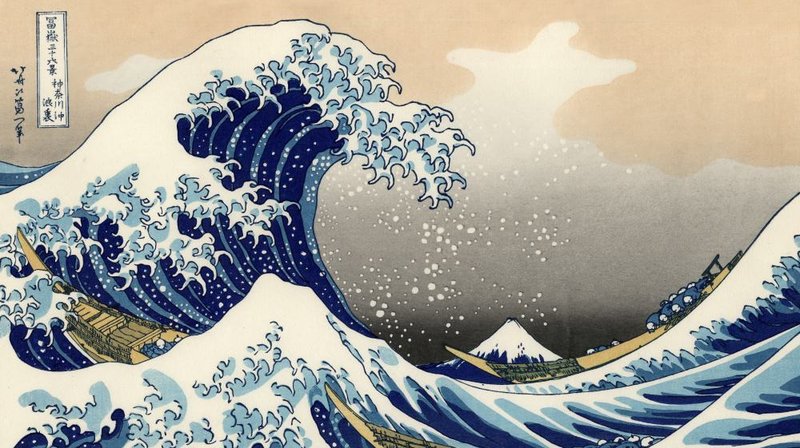

Debussy’s publisher, Jacques Durand, when describing Debussy’s study, recalled, “I … remember a certain colored engraving by Hokusai [a renowned Japanese artist; Durand is referring to Hokusai’s famous woodblock print, The Great Wave Off Kanagawa], representing the curl of a giant wave. Debussy was particularly enamored of this wave. It inspired him while he was composing La mer, and he asked us to reproduce it on the cover of the printed score.”

“From dawn to noon on the sea” reveals the effects of sunrise over the ocean. Despite the linear quality suggested in the title, Debussy’s interest was in evoking the changes of light as the sun grows stronger, rather than a depiction of time passing. In “Play of the waves,” we see/hear the ocean in different guises: calm and glassy, with sunlight shimmering on its surface; and a sudden, mercurial shift to turbulence, as whitecaps churn the water. The “Dialogue of the wind and the sea” illuminates the two natural forces of wind and water and how they interact; the movement ends with a burst of sunlight. Debussy’s penchant for Asian pentatonic (five-note) scales, rather than the conventional Western scales of European music of the time, provides an additional layer of “otherness” to the sound world he created.

Although considered a standard of the orchestral repertoire today, La mer received decidedly mixed reactions at its 1905 premiere. The negative reaction of the audience, however, had little to do with the music; rather; they hissed and booed Debussy in outrage over his scandalous private life, which had resulted in the very public suicide attempt of his wife. Camille Chevillard, who conducted the premiere, was also responsible for its poor reception. Although praised by many, including Debussy, for his abilities with established works, such as the music of Beethoven, Chevillard had little interest in or aptitude for new music. (During rehearsal for La mer, according to Simon Tresize, “Debussy complained of [Chevillard’s] lack of artistry and suggested he should have been ‘a wild beast tamer.’”) To make matters worse, bad weather on the day of the premiere kept many concertgoers away.

Critical reception also varied; La mer’s rich sonorities captivated some, while others were baffled by its lack of traditional form. Debussy subtitled the work “Three Symphonic Sketches,” but they are clearly finished movements, each with its own character. One critic wrote, “For the first time in listening to a descriptive work of Debussy’s I have the impression of beholding not nature, but a reproduction of nature, marvelously subtle, ingenious and skillful, no doubt, but a reproduction for all that … I neither hear, nor see, nor feel the sea.” In contrast, an admirer wrote, “Never was music so fresh, spontaneous, unexpected, novel rhythms; never were harmonies richer or more original; never has an orchestra possessed more voices and sonorities with which to interpret compositions overflowing with such a wealth of fantasy.”

Image: Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, c. 1829–1833.

At a Glance

- Composer: born August 22, 1862, St. Germain-en-Laye, near Paris; died March 25, 1918, Paris

- Work composed: 1903-05; Debussy wrote the date he completed La mer on the manuscript, “Sunday, March 5, 1905, at 6 o’clock in the evening.” He also arranged La mer for piano four-hands in 1905 and later revised the orchestral version in 1909. Debussy originally dedicated La mer to his lover, Emma Bardac, “For la petite mienne (small mine), whose eyes laugh in the shade.” The scandal surrounding Debussy’s private life, and his desire to shield both himself and Emma from public scrutiny, may explain why he ultimately chose to dedicate the score to his publisher, Jacques Durand.

- World premiere: La mer was first performed in Paris on October 15, 1905, with Camille Chevillard conducting the Concerts Lamoureux

- Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 cornets, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, orchestra bells, tam-tam, triangle, 2 harps, and strings.

- Estimated duration: 23 minutes

Women composers, like other female creative artists, have to fight battles their male counterparts do not. Even today, a female visual artist, writer, or composer is sometimes evaluated on criteria that have little or nothing to do with her work, and everything to do with her gender, her appearance, or her life circumstances. Lili Boulanger was no exception.

Women composers, like other female creative artists, have to fight battles their male counterparts do not. Even today, a female visual artist, writer, or composer is sometimes evaluated on criteria that have little or nothing to do with her work, and everything to do with her gender, her appearance, or her life circumstances. Lili Boulanger was no exception.

“[The Concerto in G major] is a concerto in the truest sense of the word: I mean that it is written very much in the same spirit as those of Mozart and Saint-Saëns.” – Maurice Ravel

“[The Concerto in G major] is a concerto in the truest sense of the word: I mean that it is written very much in the same spirit as those of Mozart and Saint-Saëns.” – Maurice Ravel

In 2012, the science podcast Radiolab presented an episode titled “

In 2012, the science podcast Radiolab presented an episode titled “