Posted April 1, 2019

Program Notes • Gloria

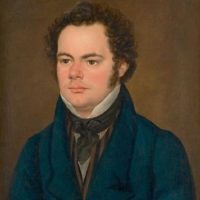

Franz Schubert

Symphony No. 7 in B minor, D. 759, [formerly No. 8] “Unfinished”

Franz Schubert’s most popular symphony remained unfinished and did not receive its first performance until more than 35 years after his death. It is interesting that Schubert, who composed eight other symphonies, a number of additional orchestral works, dramatic music, more than 600 songs, and innumerable chamber pieces, should be so renowned for a piece he failed to complete.

Why did Schubert leave this symphony unfinished? There are no surviving documents to explain why Schubert began composing this symphony: no commission, no letters, no specific event or person for whom the work was intended. At the age of 25, as he worked on the B minor Symphony, Schubert was diagnosed with syphilis, the disease that killed him six years later. He was ill, understandably depressed, and financially strapped. When he was able to work again, Schubert turned his attention to theatrical music, which, he hoped, would provide some much-needed income. Some scholars have also suggested that Schubert, whose personal standards for symphonic writing were very high, had reached a creative impasse with the B minor Symphony, based on the surviving sketches of an incomplete third movement scherzo, which do not match the quality of the first two movements. In addition, there are no extant sketches for a finale. Rather than present an incomplete work, it has been suggested, Schubert put it aside, probably intending to finish it at a later time.

Although there is no official dedication on the manuscript of the B minor Symphony, Schubert may have intended it as a thank-you to the Styrian Music Society in Graz, which had elected him an honorary member. In the fall of 1822, Schubert was informed of the award through a friend, Anselm Hüttenbrenner, a member of the Society. This corresponds with the October 30, 1822 date on Schubert’s manuscript of the B minor Symphony. Whether or not wrote the B minor Symphony specifically for the Styrian Society, Schubert did intend to send them a score, as he indicated in his thank you letter. He wrote, “In order to give musical expression to my sincere gratitude as well, I shall take the liberty before long of presenting your honorable Society with one of my symphonies in full score.” In 1823, Schubert gave the unfinished manuscript to Anselm’s brother Josef, and asked Josef to pass it on to Anselm. Schubert probably expected Anselm to turn over the manuscript to the Styrian Society, perhaps in the hope they would perform it. However, for reasons unknown, Anselm kept the manuscript; it remained in his possession, and unknown to the rest of the world, for the next 40 years.

The two movements of the B minor Symphony are unique in Schubert’s output. Both are larger and more complex than any others Schubert wrote, and they transcend the conventions of symphonic writing of Schubert’s time. Musicologist Richard Freed suggests that Schubert chose to let these two movements stand alone: “It is not too much to imagine that the genius who created this music might have recognized it at the time, as the world does now, as material so exalted that it could not be followed by anything without great risk of anticlimax.”

Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick described the Allegro moderato as “a melodic stream so crystal clear, despite its force and genius, that one can see every pebble on the bottom.” It opens with a restless theme for oboe and clarinet, accompanied by dark murmurings in the low strings. Before this theme is fully developed, Schubert abruptly switches to a gentle cello melody, but this too is interrupted by fragments of the first theme. There is a sense of barely contained impatience, as if Schubert were so full of melodic ideas that he couldn’t take the time to fully explore any of them. The fragmentary nature of this music is unusual in an early 19thcentury symphony; there is no reconciliation or final statement in which all the musical ideas are developed and transformed. Instead, Schubert juxtaposes the brooding agitation of the first melody with the calm serenity of the cello theme without any grand summation. The result is stark, innovative and unsettling. As Schubert scholar Arnold Feil noted, “Here one can see for the first time that not everything is as lovely as is generally assumed … these are in fact among the harshest and most implacable movements ever produced by Viennese Classicism in general and by Franz Schubert in particular.”

By contrast, the Andante con moto is gentleness personified … or is it? It features a lyrical conversation between the strings and a chorus of horns. As in the first movement, Schubert contrasts this music with a melody of different character, heard first in the clarinet, which is amplified by a powerful statement by the full orchestra. In this movement, Schubert begins to explore and develop these two ideas, and in so doing he moves through a bewildering variety of harmonic key areas, with a restlessness bordering on irritation. The lyricism of the string/horn theme is tinged with a longing that remains unresolved as the movement ends.

At a Glance:

- Work composed: 1822. Presumably completed on October 30 of that year, according to the date on the manuscript. It remained unpublished until 1867, and was virtually unknown for 37 years following Schubert’s death.

- World premiere: December 17, 1865. Johann Herbeck conducted the Gesellschaft die Musikfreunde [Society of Friends of Music] in Vienna

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

- Estimated duration: 22 minutes

Franz Schubert

(1797–1828)

Like a little teapot, the short-and-stout Austrian was nicknamed “Little Mushroom.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Ave verum corpus, K. 618

Simplicity is a hallmark of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s music, which pianist Artur Schnabel famously characterized as “too simple for children and too difficult for adults.” Nowhere is this more evident than in Mozart’s exquisite setting of the liturgical text Ave verum corpus. Mozart completed this short choral work (46 measures) on June 17, 1791, and it was first presented as a Eucharistic hymn in Baden at the Feast of Corpus Christi that year. Mozart dedicated the work to his friend, Anton Stoll, who was chorus master of the parish church in Baden, where Mozart was visiting with his wife Constanze.

The uncomplicated nature of the music may be based in practicality; the singers in Stoll’s parish choir were probably not first-rate musicians, so Mozart wrote music they could learn quickly and sing well. The plain language of the text may have also suggested a more basic approach. The orchestra provides the barest introduction and functions mostly as a support to the chorus, which presents the text in a manner designed to focus on the words set like jewels into shining harmonic phrases.

The original text of Ave verum corpus is based on a poem found in a 14th century manuscript from Reichenau, Switzerland. It praises the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, in which the body and blood of Jesus are transformed into the bread and wine of the Eucharist. The words also affirm the central Catholic belief in the redemptive power of suffering.

At a Glance:

- Work composed: Mozart completed Ave verum corpus on June 17, 1791

- World premiere: in Baden at the Feast of Corpus Christi on June 23, 1791

- Instrumentation: SATB chorus, organ, and strings

- Estimated duration: 3 minutes

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(1756– 1791)

Move over Honey Boo Boo — Wolfie was a child star of monolithic proportions. Having written his first 30 symphonies by the age of 18, he was the most well-known…

Wolf Durmashkin & Tobias Forster

Won’t Be Silent

Program note by composer Tobias Forster

Translated from German by Karin Tate

Wolf Durmashkin’s song, composed in a concentration camp, was performed at normal volume by fellow prisoners and then sung quietly in Yiddish. “We are silent, say not one word, mumble a prayer, nothing and no one can forbid us to weep quietly;” this is the sad, original text of the song.

The piece is in a minor key and has a very unique style. The new translation by Kara DioGuardi, “We won’t be silent,” seeks to say the opposite: We will not be silent, in order to make sure that a catastrophe such as the Holocaust can not ever come to pass again.

I try to bring two extremes: sadness & pain and hope & joy into harmony in my transcription for orchestra and chorus.

The introductory measures in the strings depict the hopelessness of the situation in the camp at that time. Throughout the composition, the melody is repeated numerous times, although each time in a different musical context.

While composing, I let myself be led by my emotions which illuminated the original song. A sad melody set against a tragic background… to express this in a somewhat more hopeful mood was a challenge. In taking the melody apart into separate pieces, some associations became apparent. It contains, barely hidden, the “dies irae” motif, a part of Chopin’s “Funeral March,” and elements of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” The harmony expressed in the first two measures is exactly that of the first four measures of Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden.” In the development of the original melody, I used these elements, combining and transforming them. The clarinet solo is an homage to Ashkenazi Jewish klezmer music.

After the broad but somewhat ironic climax in a major key, the original melody returns to be embraced and remembered.

Wolf Durmashkin

(1914–1944)

While detained in the Vilna Ghetto, Wolf smuggled in instruments — including a piano! — and started the Ghetto Orchestra which performed 35 concerts attended by the Nazis before he…

Tobias Forster

(b. 1973)

Dresden-based composer and pianist Tobias Forster’s artistic focus is on solo concerts and creative collaboration with musicians of various origins. Classical and jazz, as well as their fusion, play an…

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mass in C minor, K. 427 (K. 417a), “The Great”

It is a romantic notion that the finest music is always created from some profound wellspring of inspiration, while music written for a commission is, by definition, inferior. In fact, Mozart wrote some of his best works for money. Most of Mozart’s music, including all but one of his religious compositions, were written for the Archbishop of Salzburg, or patrons in Vienna, or (like his piano concertos), for subscription concerts he presented in hopes of attracting large paying audiences.

Mozart’s Mass in C minor is the exception. Mozart had a strong personal motivation for composing it, but his impetus is unknown. From letters Mozart wrote to his father Leopold, we know that the Mass was written to fulfill a promise Mozart had made; the nature of that promise, however, is not clear. Some scholars suggest the Mass is Mozart’s expression of joy upon his marriage to Constanze Weber. Others say Mozart made a vow to his father that he and Constanze would visit Salzburg, and the Mass is proof of Mozart’s intention to fulfill that vow. According to Constanze, Mozart composed the Mass as a thanksgiving offering for Constanze’s safe delivery of their first child, Raimund. Whatever the reason, the Mass clearly meant a great deal to Mozart. In a letter dated January 3, 1783, Mozart wrote to Leopold, “It is quite true about my moral obligation, and indeed I let the word flow from my pen on purpose. I made the promise in my heart of hearts and hope to be able to keep it … the score of half of a mass, which is still lying here waiting to be finished, is the best proof that I really made the promise.”

And yet, for all its personal significance, Mozart did not complete the Mass in C minor. When it was first performed in October 1783, only the Kyrie, Gloria, parts of the Credo and Sanctus were finished. Since the Mass was being presented as part of a regular church service, and not as a concert piece, Mozart would have had to fill in the missing sections (most of the Credo and the Agnus Dei) with other music, possibly his own, or perhaps with plainchant from the Catholic liturgy.

Stylistically, the Mass in C minor is a mixture of old and new, liturgical and secular. In 1782, Mozart, under the influence of one of his patrons, Baron Gottfried van Swieten, immersed himself in the music of Handel, J. S., and C.P.E. Bach. The Baroque contrapuntal style of these earlier masters found its way into Mozart’s religious music, particularly the Kyrie and the “Qui tollis” and “Cum Sancto Spiritu” in the Gloria. Other sections, most notably the “Et incarnatus est” from the Credo, are clearly operatic, incorporating the vocal agility and intimacy of Italian opera.

Theories abound as to why Mozart left this Mass unfinished. Annotator Nick Jones noted, somewhat wryly, “Of all [Mozart’s] religious works, the C minor Mass is the only one not written in response to a commission or request. Its commissioner was Mozart himself, and he was not a sufficiently insistent patron to compel the work’s completion.” There is also the contention of Alfred Einstein, one of Mozart’s biographers, that all the music Mozart wrote for Constanze is incomplete, with its misogynist inference that Constanze was somehow responsible for that fact.

Austrian composer Helmut Eder, who adhered to Mozart’s sketches and instructions closely when he realized the unfinished sections of the Mass, completed the Barenreiter Edition of the Mass used in tonight’s performance.

At a Glance

- Work composed: Summer 1782 – October 1783

- World premiere: The Kyrie, Gloria, parts of the Credo, and the Sanctus of the Mass were first performed at the Church of St. Peter’s Abbey in Salzburg on Oct. 26, 1783. Mozart’s wife Constanze sang the soprano solos.

- Instrumentation: 2 soprano soloists, solo tenor, solo bass, SATB choir, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, organ, and strings

- Estimated duration: 80 minutes

Elizabeth Schwartz

Author

Elizabeth Schwartz is a freelance writer, musician, and music historian based in Portland. She provides notes for ensembles across the United States and around the world, including the Oregon Symphony…

© 2019 Elizabeth Schwartz

These program notes are published here by the Denver Philharmonic Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com.