Our 71st Season kicks off September 28 with two heroes of symphonic music: Niccolò Paganini and Ludwig van Beethoven. Written only about 15 years apart from each other, each piece deified the composers in their own right. Paganini wrote the concerto for himself — basically to show off his mad violin skillz — and Beethoven’s “Eroica” has been named the greatest symphony of all time.

Descarga las notes del programa en español

Buy Now for Heroes

Program Notes • Heroes

Niccolò Paganini

Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 6

The emerging romanticism we associate with 19th-century music changed both composers and performers alike. One basic aspect of Romanticism is its emphasis on individual experience. Early romantic composers like Ludwig van Beethoven, and later Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann, embraced opportunities for particular self-expression that were unique to their lived experiences. In Schubert’s case, his exploration of harmonically unusual tonalities gave voice to emotions and moods never before heard in music.

Romanticism allowed composers to prioritize their individual artistic explorations, but the interest in personal expression also gave rise to an entirely new type of performer: the superstar virtuoso. Of all the outstanding instrumentalists who emerged in the 19th century, none could match the sheer technical brilliance or the commanding ego of Niccolò Paganini, the first of this new breed.

There were other great violinists before Paganini, but the musical and artistic aesthetics of their time limited their ability for self-expression. Before Paganini, performers, no matter how skilled, played in the service of their music. They were the interpreters, and it was the music that took center stage.

From his debut performance at age 11 in Genoa, Italy, Paganini exploded the idea that the performer should take a back seat to the music he played. For more than 30 years, Paganini cultivated a new kind of musician: a superstar, with a devoted following who came to hear him play, regardless of repertoire. Everything Paganini did in performance — his penchant for performing all in black, his carefully disheveled hair and clothes, and especially his over-the-top stage mannerisms — was deliberately planned so as to achieve a certain effect: the creation of Paganini the Romantic artist. He was one of the first artists to craft a cult of personality and mystery to accompany his virtuoso playing.

Today superstars are common enough in both music and art, and some trade on their charisma to cover up less-than-first-rate skill. His manufactured mystique notwithstanding — Paganini never allowed anyone to hear him practice, for example — Paganini lived up to his own hype. There seemed no limit to his facility on the violin, nothing too difficult or technically unconventional that he could not master. Paganini became known for his left-handed pizzicato notes, and a technique he called the “ricochet,” where he bounced the bow quickly across the strings. Most dazzling of all, Paganini executed flawless runs of double-stop harmonics at lightning speed, a skill that left other violinists shaking their heads in admiration.

After he had run through all the suitably virtuoso works in his repertoire — and after a request for a piece by Hector Berlioz resulted in Harold in Italy, which Paganini deemed insufficiently virtuosic for his style of playing, Paganini began composing his own music to create showpieces for his skill. The Violin Concerto No. 1, originally written in E-flat, required the soloist to tune his violin up a half step. The higher pitch allowed for a more brilliant tone, but over time most musicians and orchestras have chosen to perform it in D, a more natural key for the violin (and easier to keep in tune).

As a vehicle for Paganini, the Violin Concerto provides everything a virtuoso would want: plenty of dazzling runs and other lightning-fast tricks, and a clear emphasis on the soloist — the orchestra takes a secondary role as accompanist. Additionally, as in the central Adagio, the music gives the soloist an opportunity to demonstrate lyricism and refined tone. Paganini wanted to dazzle his audience, but he also wanted to move them. He succeeded with Schubert, who, having heard Paganini in Vienna, described his playing as “the singing of an angel.”

At a Glance

- Work composed: 1816–18

- World premiere: March 31, 1819, in Naples, Italy, with Paganini performing the solo part

- Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (1 doubling contrabassoon), 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, and strings

- Estimated duration: 35 minutes

Niccolò Paganini

1782–1840

Italian composer and violinist Niccolò Paganini never allowed anyone to listen to him practice. This heightened the mystique surrounding his persona and fed the rumors that Paganini had sold his…

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55, “Eroica”

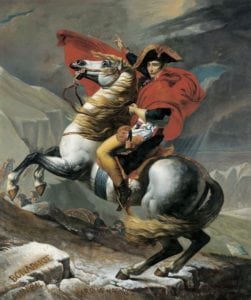

Ludwig van Beethoven was an early admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose early exploits as First Consul of France reaffirmed the motto of the French Revolution, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” It had been Beethoven’s intention to dedicate his third symphony to Napoleon, but when Beethoven heard that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor in May 1804, he was outraged. So vehement was Beethoven’s desire to rid his third symphony of any association with the French general that he erased the words “intitulata Bonaparte” from the title page with a knife, which left a hole in the paper. When the score was first printed in 1806, the title page read only, “A heroic symphony … composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

Ludwig van Beethoven was an early admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose early exploits as First Consul of France reaffirmed the motto of the French Revolution, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” It had been Beethoven’s intention to dedicate his third symphony to Napoleon, but when Beethoven heard that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor in May 1804, he was outraged. So vehement was Beethoven’s desire to rid his third symphony of any association with the French general that he erased the words “intitulata Bonaparte” from the title page with a knife, which left a hole in the paper. When the score was first printed in 1806, the title page read only, “A heroic symphony … composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

Today, the Eroica is considered one of the groundbreaking musical events of the 19th century, but in Beethoven’s time it received a great deal of criticism. Its length alone challenged the audience (depending on the conductor’s tempos and observations of marked repetitions in the score, the Eroica runs 45–60 minutes). Beethoven acknowledged this, noting in the 1806 edition of the score, “This symphony being purposely written much longer than is usual, should be performed nearer the beginning rather than at the end of a concert … if it is heard too late it will lose for the listener, already tired by previous performances, its own proposed effect …”

One critic complained, “In this composition [there is] too much that is glaring and bizarre, hindering greatly one’s grasp of the whole.” Another reviewer, using words that today we would consider praiseworthy, criticized Beethoven’s “undesirable originality.” The critic went on to say, “Genius proclaims itself not in the unusual and fantastic but in the beautiful and sublime” and further, that the symphony as a whole was “unendurable to the mere music-lover.” From our vantage point at the beginning of the 21st century, we can recognize Eroica’s importance. Similar in its impact to Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the influence of Eroica reverberated in all the symphonic music of the century that followed it.

Beginning with the one-two punch of the opening chords of the Eroica, Beethoven obliterated the concept of the Classical-style symphony and earned for himself the adjective “revolutionary.” Everything about this lengthy first movement confounds expectation: its unexpected and continuous development of melodic fragments, its “wrong key” tonalities, and Beethoven’s idiosyncratic use of rhythm, which at times verges on the eccentric. Certainly this was shocking to audiences accustomed to the more predictable pace of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn. Of particular note is the notoriously “early” entrance of the horn towards the end of the first movement.

Beethoven’s student and biographer Ferdinand Ries recalled, “At the first rehearsal of the Symphony, which was terrible — but at which the horn player made his entry correctly — I stood beside Beethoven and, thinking that a blunder had been made I said: ‘Can’t the damned hornist count? — it sounds horribly false!’ I think I came pretty close to getting a box on the ear. Beethoven did not forgive that little slip for a long time.”

The solemn, majestic Marcia funebre (funeral march) can be heard as Beethoven mourning his disappointment in Napoleon, and his vanished dreams of heroism.

The buoyant Scherzo and trio leaves the intensity of the previous two movements behind. Here is Beethoven’s mocking sense of humor at play, as when the strings return with their signature theme and stomp all over their previously playful rhythm. The insistent pulse of the strings and the incessant bounce of this movement continue the Eroica’s enormous reserves of energy; the music is like a puppy chasing its own tail.

The final movement, a set of themes and variations, uses music from the Beethoven’s own Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus from 1801 and an 1802 solo piano work, known today as the Eroica Variations. A virtuoso blast from the horn section signals the symphony’s conclusion, a glorious reaffirmation of Beethoven’s heroic ideals.

At a Glance

- Work composed: 1802-04. Dedicated to Beethoven’s patron, Prince Franz Joseph Maximilian Lobkowitz.

- World premiere: Beethoven conducted the premiere on April 7, 1805 in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 3 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani and strings.

- Estimated duration: 47 minutes

Ludwig van Beethoven

1770–1827

One of the most famous composers of all time, Ludwig van Beethoven broke the mold of the Classical-era style of music. His popularity never waned influencing musicians from Billy Joel…

Elizabeth Schwartz

Author

Elizabeth Schwartz is a freelance writer, musician, and music historian based in Portland. She provides notes for ensembles across the United States and around the world, including the Oregon Symphony…

© 2018 Elizabeth Schwartz

These program notes are published here by the Denver Philharmonic Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com.