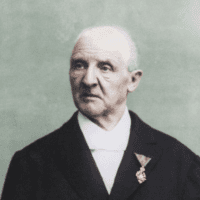

Anton Bruckner

Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, “Romantic”

Anton Bruckner was deeply insecure, highly sensitive to criticism, and full of self-doubt. Rarely satisfied with his music, even after publication, Bruckner’s incessant tinkering produced multiple versions of several of his symphonies, including the Fourth, which Bruckner subtitled “Romantic” some time after its completion.

The original version of the Fourth Symphony was finished in 1874. The Vienna Philharmonic rehearsed it the following year but refused to perform it, claiming only the first movement was worth playing. Despite his disappointment at this harsh verdict, Bruckner took the criticism to heart. Over the next five years, he refashioned the Fourth Symphony, replacing the third movement and rewriting the finale twice. This version, the one you will hear tonight, was first performed by the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter, on February 20, 1881. Bruckner made still further revisions to the Fourth Symphony in the mid-late 1880s. To further complicate matters, two of Bruckner’s students also made changes to the Fourth Symphony, (some without Bruckner’s consent), which were included in the 1889 published version.

Bruckner was seen by many as a country bumpkin from northern Austria whose unsophisticated manners amused the cosmopolitan Viennese. Bruckner’s naïveté also got him into trouble. He had no interest in getting involved in the great musical war that raged in Vienna between Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms and their followers. However, by expressing admiration for Wagner’s music, and by incorporating aspects of Wagnerian style into his own music, Bruckner unintentionally made himself a target for the anti-Wagnerites, none of whom was more acid-tongued than the influential critic Eduard Hanslick. When the Fourth Symphony premiered in 1881, Hanslick wrote, “This paper has already reported on the extraordinary success of a new symphony by A. Bruckner. We can only add today that, on account of the respectable and sympathetic personality of the composer, we are very happy at the success of a work which we fail to understand.” Hanslick’s curled-lip disdain notwithstanding, the audience warmed to Bruckner’s music, calling him to the stage for bows after each movement.

A solo horn intones a soft call over tremolo strings as the first movement begins. The woodwinds echo it and maintain the hushed atmosphere as the harmonies slide in and out of E-flat major. A five-note ascending melody first heard in the violins and flutes, is the basis of the primary theme of the first movement. This scrap of melody merges duple and triple meters (of the five quarter notes, the first two are in duple meter and the last three are grouped together as a triplet), and became so identified with Bruckner that today it is known as the “Bruckner rhythm.” It is this rhythm, more than any particular melody, which defines the first movement. The strings present a discrete counter-theme is first presented by the strings, and Bruckner spends the bulk of the first movement delving into the rhythmic, melodic and harmonic possibilities of these two melodies. The horns reiterate their opening hunting call as the movement ends.

The cello melody that begins the Andante is both funereal and majestic, and the cellos are accompanied by the soft, persistent footfalls of the violins. (Later, when the violas take over the cello melody, the marching of the funeral cortège is heard in pizzicato strings). An expansive string chorus reiterates the solemnity of this melody. Harmonically, Bruckner begins in the somber key of C minor, and he returns to it periodically throughout. As the movement progresses, however, Bruckner ranges far and wide, through a series of tender harmonies that suggest the mourners’ happy recollections of the deceased, or perhaps religious musings on the departed soul. The movement ends with the brasses’ unequivocally triumphant restatement of the original theme, after which the sober mood of the opening is briefly reestablished.

Horns announce the Scherzo with a bold fanfare, signaling the start of a hunting expedition. The heroic brass fanfares, and the “Bruckner rhythm,” sound several times, as the hunters pursue their quarry. In his manuscript for the first edition of the score, Bruckner marked the trio’s quieter interlude, with its leisurely melody for winds, as “Dance tune at mealtime on the hunt.”

The exuberance of the Scherzo is swallowed by the tension-filled introduction to the Finale. It builds to a portentous full orchestra blast of E-flat minor, and this ominous theme uses the “Bruckner rhythm” to propel itself forward like an engulfing wave. As the wave subsides, another mournful C minor melody recalls the Scherzo. Bruckner’s harmonies slide without pause in and out of major and minor keys, which continually changes both mood and pace. This movement is the most varied of the four. It takes us on a circuitous, rambling (but never random) journey, replete with charismatic music and abrupt transitions. The brilliant final coda exposes Bruckner’s underlying belief in the validity of his musical vision.

At a glance

- Composer: born September 4, 1824, Ansfelden, near Linz; died October 11, 1896, Vienna

- Work composed: First version completed in 1874 but rejected by the Vienna Philharmonic. Over the next five years, Bruckner made substantial revisions.

- World premiere: The Vienna Philharmonic performed the 1880 version under Hans Richter, on February 20, 1881

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

- Estimated duration: 65 minutes