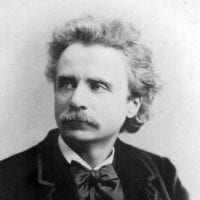

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

In 1853, Robert Schumann wrote a laudatory article about a 20-year-old composer from Hamburg named Johannes Brahms, whom, Schumann declared, was the heir to Beethoven’s musical legacy.

Schumann wrote, “If [Brahms] directs his magic wand where the massed power in chorus and orchestra might lend him their strength, we can look forward to even more wondrous glimpses into the secret world of the spirits.” At the time Schumann’s piece was published, Brahms had composed several chamber pieces and works for piano, but nothing for orchestra. The article brought Brahms to the attention of the musical world, but it also dropped a crushing weight of expectation onto his young shoulders. “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea how it feels to hear behind you the tramp of a giant like Beethoven,” Brahms grumbled.

Because Brahms took almost 20 years to complete what became his Op. 68, one might suppose its long gestation stemmed from Brahms’ possible trepidation about producing a symphony worthy of the Beethovenian ideal. This assumption, on its own, does Brahms a disservice. Daunting though the task might have been, Brahms also wanted to take his time. This measured approach reflects the high regard Brahms had for the symphony as a genre. “Writing a symphony is no laughing matter,” he remarked.

Brahms began sketching the first movement when he was 23, but soon realized he was handicapped by his lack of experience composing for an orchestra. Over the next 19 years, as he continued working on Op. 68, Brahms wrote several other orchestral works, including the 1868 German Requiem and the popular 1873 Variations on a Theme by Haydn (aka the St. Anthony Variations). The enthusiastic response that greeted both works bolstered Brahms’ confidence in his ability to handle orchestral writing. In 1872, Brahms was offered the conductor’s post at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music). This opportunity to work directly with an orchestra gave Brahms the invaluable first-hand experience he needed. 23 years after Schumann’s article first appeared, Brahms premiered his Symphony No. 1 in C minor. It was worth the wait.

Brahms’ friend, the influential music critic Eduard Hanslick, summed up the feelings of many: “Seldom, if ever, has the entire musical world awaited a composer’s first symphony with such tense anticipation … The new symphony is so earnest and complex, so utterly unconcerned with common effects, that it hardly lends itself to quick understanding … [but] even the layman will immediately recognize it as one of the most distinctive and magnificent works of the symphonic literature.”

Hanslick’s reference to the symphony’s complexity was a polite way of saying the music was too serious to appeal to the average listener, but Brahms was unconcerned; he was not trying to woo the public with pretty sounds. “My symphony is long and not exactly lovable,” he acknowledged. The symphony is carefully crafted; one can hear Brahms’ compositional thought processes throughout, especially his decision to incorporate several overt references to Beethoven. The moody, portentous atmosphere of the first movement, and the short thematic fragments from which Brahms spins out seemingly endless developments, are all hallmarks of Beethoven’s style. Brahms also references Beethoven by choosing the key of C minor, which is closely associated with several of Beethoven’s major works, including the Fifth Symphony, Egmont Overture, and Piano Concerto No. 3. And yet, despite all these deliberate nods to Beethoven, this symphony is not, as conductor Hans von Bülow dubbed it, “Beethoven’s Tenth.” The voice is distinctly Brahms’, especially in the inner movements.

The tender, wistful Andante sostenuto contrasts the brooding power of the opening movement. Brahms weaves a series of dialogues among different sections of the orchestra, and concludes with a duet for solo violin and horn. In the Allegretto, Brahms relaxes Beethoven’s frantic scherzo tempos. The pace is relaxed, easy, featuring lilting themes for strings and woodwinds. The finale’s strong, confident horn solo proclaims Brahms’ victory over the doubts that beset him during Op. 68’s long incubation. Here Brahms also pays his most direct homage to Beethoven, with a majestic theme, first heard in the strings, that closely resembles the “Ode to Joy” melody from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When a listener remarked on this similarity, Brahms snapped, “Any jackass could see that!”

At a glance

- Composer: born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna

- Work composed: Brahms began working on his first symphony in 1856 and returned to it periodically over the next 19 years. He wrote the bulk of the music between 1874 and 1876.

- World premiere: Otto Dessoff led the Badische Staatskapelle in Karlsruhe, on November 4, 1876.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

- Estimated duration: 42 minutes