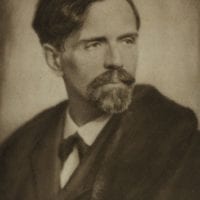

Zoltán Kodály

Háry János Suite

“The voice of Kodály in music is the voice of Hungary.” – Sir Arthur Bliss

In 1905–06, Zoltán Kodály traveled to the far corners of Hungary collecting and recording folk music on wax cylinders. During this time, he also became acquainted with Béla Bartók. The two men shared a passion for Hungarian folk idioms, and Kodály taught Bartók his methods for collecting and preserving their country’s indigenous music. The time both men spent immersed in this ethnomusicological work also had a profound influence on their own compositions; Bartók tended to write original folk-inflected music, while Kodály often combined a mixture of pre-existing folk tunes and his own inventions.

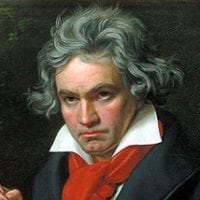

In 1926, Kodály featured this blend of original and indigenous music in his singspiel (operetta) about Háry János, a historical figure from the early 19th century. János, a foot soldier in the Austrian army’s fight against Napoleon, had a knack for embellishment, and later claimed the rank of general. After the war, János returned to his village and regaled his friends with a series of colorful tales about his “adventures.”

“Day after day he sits in the tavern and recounts his incredible heroic feats,” wrote Kodály about János. “He is a true peasant, and his grotesque inventions are a touching mixture of realism and naiveté, of comedy and pathos. All the same, he is not just a Hungarian Baron Munchausen. On the surface, he may appear to be no more than an armchair hero, but in essence, he is a poet, carried away by his dreams and feelings. His tales are not true, but that is not the point. They are the fruits of his lively fantasy, which creates for himself and for others a beautiful world of dreams … We all dream of the great and impossible. Few of us master, like Háry, the courage to utter our dreams.”

Kodály chose six movements from the complete singspiel for the orchestral suite he made in 1927. The Prelude, titled “The Fairy-tale Begins,” opens with a gigantic orchestral sneeze, indicating the fantastic nature of what follows. The music features an expansive, heroic theme, suggestive of a 1930s film score. This ends abruptly with the chiming of the Viennese Musical Clock and a jaunty march. For the Song, Kodály chose an existing folk melody, “Tiszán innen, Dunán túl” (This side of the Tisza), from Háry János’ birthplace, Tolna County. We first hear a solo viola, followed by several variations. The melody’s plaintive quality is enhanced by the inclusion of the cimbalom, an eastern European hammered dulcimer, in the accompaniment. The Battle and Defeat of Napoleon features military instruments, particularly brass and percussion, to convey the epic conflict between Napoleon’s army and that of Holy Roman Emperor Franz II. The French forces march to a distorted parody of “La Marseillaise,” and, in a revisionist version of historical events, Kodály accompanies Napoleon’s “funeral” with a mournful saxophone. The cimbalom returns in the Intermezzo, a verbunkos. This most popular Hungarian dance is known for its offbeat accents, as well as contrasting slow (lassú) and fast (friss) sections. The march of the Entrance of the Emperor and His Court is appropriately gaudy, bedizened with sparkle and brilliant colors that end the Suite with a dazzling flourish.

At a Glance

- Composer: born December 16, 1882, Kecskemét, Hungary; died March 6, 1967, Budapest

- Work composed: 1926-27

- World premiere: March 24, 1927, by the Pau Casals Orchestra in Barcelona, led by Antal Fleischer

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (all doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (1 doubling alto saxophone), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, celesta, chimes, cymbals, glockenspiel, tambourine, tam-tam, triangle, xylophone, piano, cimbalom, and strings

- Estimated duration: 25 minutes